The desensitization of mass shootings

February 5, 2019

Last year, there were 340 mass shootings in America. That’s an average of almost one every day. Yet, many of them didn’t even make national headlines. As the years have gone by, it seems as though mass shootings have become so common that we don’t react to them the way we used to.

What once used to be an appalling incident has become a frequent and only mildly shocking occurrence that doesn’t even consistently get news coverage anymore. As it has become more frequent, we haven’t realized that there once was a time not too long ago when mass shootings were almost unheard of. We have become so desensitized to mass shootings that we have forgotten to demand change.

Mass shootings are defined by shootings in which four or more people are shot and killed or injured, not including the shooter, and there have been even more shootings that don’t fit this set of qualifications. As of Feb. 26, there have been 47 mass shootings in 2019 alone.

For those with loved ones who have died from gun violence, or the survivors who made it out alive, the day of the shooting will forever be etched into their memories. Meanwhile, for the rest of us, it’s another instance of an increasingly common tragedy that we have become far too accustomed to. It still horrifies and shocks us, but we move on with our lives quickly, often without nearly enough of a second thought. We know it’s only a matter of time until the next one, but nobody ever thinks it could happen to them.

There may be a psychological reason that explains our decreased response to mass shootings. Charles Figley, the director of the Traumatology Institute and a professor of social work at Tulane University, observed the response to the Parkland shooting.

“There are two primary methods of dealing with a traumatic event: to respond, or to put it out of your mind. That’s what’s happening now,” Figley said. “We’re still shocked, but we watch the people in the communities where this has happened, and we see their shock, their unpreparedness. We think, ‘There is nothing they could have done.’ The more frequently this happens, the more it reminds people there’s nothing they can do, so they put it out of their minds.”

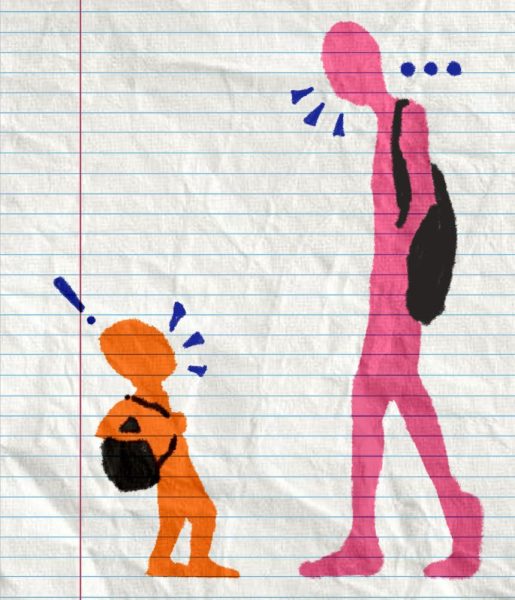

Additionally, one lab study was able to measure desentization in subjects who were exposed to varying levels of media violence. When referring to this study, Traci M. Kennedy, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, stated, “Those who are assigned to view higher levels of violence do show signs of desensitization, even within a few hours. They become habituated to the violence, they’re less scared or just less responsive, and show lower levels of empathy toward the victims.” It seems that our change in response may very well be psychological, and astonishingly enough, we are somehow becoming less sympathetic to victims as shootings occur more frequently.

If we continue to accept that mass shootings will always be a constant in our country, then how can we ever hope to makes the changes we need to in order to prevent it? If shootings don’t even become national news until a “significant” amount of people die, then how will we ever realize that even one, two, or three deaths or even injuries from a shooting is more than there ever should be?

If our own emotional reactions are blocked in response to such horrific events, how can we ever again fully realize the magnitude of the problem? The desensitization of mass shootings is a much more important issue than previously thought, as they are leading us to minimize the extent of the horrific event that occurs. Until we deem mass shootings as absolutely unacceptable, we destroy any hope of one day living in a world without them.