At what birthday was getting older not exciting anymore?

When I ask this, I operate under the same assumption Coralie Fargeat does in her newest body-horror film The Substance – that your excitement, or even indifference, for aging was wrecked and replaced with some sense of dread a while ago. And, with that theory, Fargeat crafts a freakish look into the aging process as a celebrity past her prime (Demi Moore as Elisabeth Sparkle) clings onto stardom by using, and eventually abusing, a black market drug that creates a younger variant of her (Margaret Qualley as Sue).

That last bit sounded like a lot, but the film actually does a good job at explaining how the eponymous substance works without taking up too much dialogue. Sparkle receives a box that instructs her: She can activate this variant only once, only her or her variant can be conscious at a time, they must switch back and forth every seven days, and to remember that even though they don’t share a mind, they are still one entity. Sparkle resorts to the substance after being fired from her aerobic instructor gig because her boss (Dennis Quaid as Harvey) wanted a younger face to replace her. After a messy activation, Sue aims to be this very replacement.

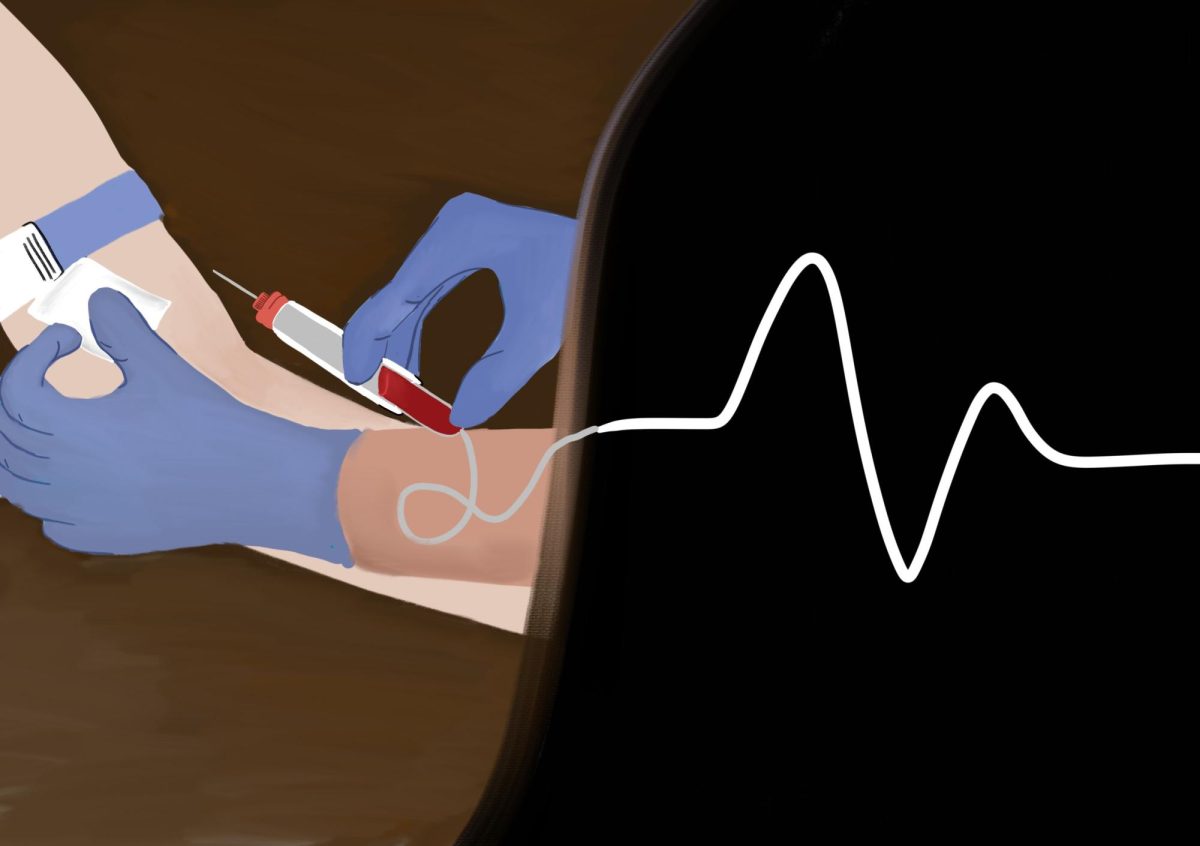

A key consequence of Sparkle misusing the substance is that the longer Sue carries on past her designated seven days, the faster Sparkle ages. Eventually, she becomes an unrecognizable caricature of the elderly. Fargeat goes all out to hone in on the disgust Sparkle feels with endless close-ups of needles, injections, open wounds, and curates a distressing time for anyone in the audience. As Sue and Sparkle adapt to their new routine, though, the viewer accommodates to being repulsed, and each infected-gash-close-up gets less shocking than the one that came before it.

But between the extremes of a regular 50-year-old woman and a monster so ugly it’s not even human-looking anymore, exist many non-exaggerated, realistic versions of an aging Sparkle that the audience is meant to laugh and squirm at. For a lot of these intermediate parts, the “monstrous,” aged version of Sparkle may even look like someone you know. It takes a while for the movie to break out of a repetitive rut of showing Sparkle looking and acting old while Sue looks and acts young. At times, the deliberate cruelty Fargeat treats Sparkle with becomes the scariest aspect of the film.

There’s the argument that this film takes place from the perspective of the relentless industry Sparkle gets spit out of – that it’s not Fargeat that’s looking down on her, but rather, the Hollywood producers that would consider Sparkle a monstrosity when she ages. But because the film spends so much time in the middle, after Sparkle develops her insecurities but before the excessiveness of any real body-horror, the message gets lost. If Fargeat didn’t wait until the end to go all out, she could better exaggerate the judgemental attitudes of the producers she wants to ridicule. But just showing a typical old lady and framing her as if she’s grotesque doesn’t really say anything worthwhile, and Fargeat’s limbo in the center puts her next to the people she’s attempting to critique by making a mostly normal female aging process the undeserved punchline.

During her seven days in control, Sue ends up loving her life as Harvey’s newest star, while Sparkle descends into self-loathing any moment she’s awake. Unfortunately, all there is to Sue is an unwavering desire to get on TV, which she accomplishes almost immediately, but we don’t really get to see why Sue/Sparkle wanted this so much to begin with. Ultimately, it’s up to the viewer to assume what about stardom was so appealing for her and that takes away an avenue to make these characters feel more human. Sue, Sparkle, and Harvey don’t feel like people as much as they feel like dolls made to mouth dialogue, and it’s hard to care about that for a 140-minute runtime already weighed down with redundant chunks in the middle.

At its best, The Substance is a grotesque, funny, over-the-top look into a fast-paced industry that exploits women’s fear of aging and loses appreciation for them once they’re deemed “old.” At its worst, it starts to agree with that very industry.